for Server User-Agents

Notes from the 41st IIW

I just got back from the 41st IIW (Internet Identity Workshop) and 1st AIW (Agentic Internet Workshop). It really was incredible, and so many thanks to Kaliya, Jim, and everyone else who created, and continues to nurture such a special and important event. It was my first time to the event, but I felt welcomed like family, and already feel like I will be friends with many of the people I met for a long time.

For those who just want to know WTF a Server User-Agent is, skip ahead.

Years ago, I had a friend who ran an open mic comedy night and often encouraged me to come out. I had young kids at the time and it dominated my evenings, but I managed to make it out one night. I had barely sat down to enjoy myself when he came by and pressured me to go up that night and do a couple jokes off the dome. I’d never done standup before, but I enjoyed it and so instead of paying attention to the first few acts I started working on some jokes, and when I thought I had something I signed up for a slot in the lineup. I didn’t exactly kill, but I got some laughs and I was told I had good timing. A lifetime of stories like this one have encouraged me to be a little bold when I enter new spaces or try new things.

So of course, coming to my first IIW (or unconference of any kind), I had to do a session. For those unfamiliar, the unconference approach means that the attendees are the ones who make the agenda and run all the sessions. Not only that, though, these agendas aren’t set until the morning of each day of the conference. In a totally open, and self-organizing fashion, attendees create session topics, schedule them on a big board, and then spend the day going to each others’ sessions. Its a fantastic, direct, and responsive way to get many excited nerds (and non-nerds) to coordinate, share, collaborate, and take feedback on a very niche seeming topic like digital identity on the internet.

I already knew what I wanted to talk about. The topic of this article: Server User-Agents. I had a mission to start a movement and so I grabbed my first session card and titled it: “Server User-Agents: A fundamental missing piece of infrastructure”. I did my best 30 second pitch and then joined the eventual mosh pit of a self-organizing agenda. I’d learned that fortune favors the bold, and so in the heat and chaos of a rapidly filling schedule wall, I decided to just go for slot 1. Why *not* lead for my first ever session? This way I had no expectations to compare to. And why not spread the gospel early? If I’ve only got a snowball’s chance in hell, I might as well start rolling early and get the biggest damned snowball I can make.

I had no slide deck or even notes. I just wanted straight conversation with people about a concept that I thought was probably on the tip of nearly everyone’s tongue’s already. At first the audience was pretty small. I started by just drawing a simple diagram and naming some concepts. My rhetoric game was still in the earliest workshopping.

I hadn’t anticipated how much the hype of AI Agents would affect what people imagined when they heard “Server User-Agent”, for good or for ill. Nevertheless, I persisted —answering questions, and collaboratively whiteboarding until the group was satisfied with the premise. I had the beginner’s luck of having my first session in a relatively public space, and over the course of the hour, a lot more people drifted through, curious at the passionate discourse. Over the next four days I would learn better how to communicate the vision and relate to the many existing endeavors my other attendees and ongoing standards work.

I wasn’t alone at the workshop, and my co-founder Swan was also throwing hands in the mix. Together we embraced, and were embraced, by the passionate community — attending sessions and demos, as well as leading four more of our own (including a couple more on Server User-Agents). The days extended into nights, with some of the best conversations happening after-hours.

By the end of the week, “Server User-Agent” (or SUA for short) had become a term other folks were adopting, and a Signal group chat was formed which will likely become a working group in time. I closed out my own time at the workshop by playfully announcing that, “Years from now, you will remember this workshop as when you first heard of Server User-Agents.”

I know, I know, it’s dramatic. What can I say, I’m a Libra.

Before I move on, I just want to thank, again, all of the wonderful personalities I met last week. It was incredible to be able to dive right into deep topics quickly and lightly spar on purpose and approaches. I learned a lot, and my articulation of the concept here today is made much better by projects like the First Person Project, SideWays.earth, MyTerms, CAWG, and “the silly stack”. It is only now viable for SUA’s because of the hard work making specs for things like Verifiable Credentials and DIDs that are enabling a better future. And finally, it is my hope, that Server User-Agents help crystallize the solution for making “Bring Your Own Everything” actually “Effortless”, and making local-first solutions easily scale to work just as easily remotely.

I’ve managed to come this far without explaining directly what a Server User-Agent is, but hopefully by now you’re chomping at the bit for me to explain it in the next section.

What is a User-Agent?

Ok, I tricked you. I have to explain what a User-Agent is first. If you triple promise me you know what a user agent is and don’t need additional context, you can skip ahead, but don’t come crying to me later if you get confused because you miss all this rad and profound context that I’m about to lay down.

While its rapidly becoming obsolete and obscure knowledge, for most people who have even heard the term “user agent”, it has likely been in reference to the user-agent string sent in the header of HTTP requests by browsers. Or maybe, just for fun, you’ve read the HTTP spec and seen it used a few dozen times. Either way, the most common meaning of the term “user agent” is simply “web browser” or “email client”. This is good enough most of the time, but lacks the deeper meaning and design principles that lead to the use of the term as opposed to simply “client” or “program”.

To gain this deeper meaning, I think a good place to start is the Web Platform Design Principles document created by the W3C. In particular, principle 1.1, “Put user needs first”.

Priority of Constituencies

This is the text from Principle 1.1, the very first principle (emphasis mine):

1.1. Put user needs first (Priority of Constituencies)

If a trade-off needs to be made, always put user needs above all.

Similarly, when beginning to design an API, be sure to understand and document the user need that the API aims to address.

The internet is for end users: any change made to the web platform has the potential to affect vast numbers of people, and may have a profound impact on any person’s life. [RFC8890].

User needs come before the needs of web page authors, which come before the needs of user agent implementors, which come before the needs of specification writers, which come before theoretical purity.

Like all principles, this isn’t absolute. Ease of authoring affects how content reaches users. User agents have to prioritize finite engineering resources, which affects how features reach authors. Specification writers also have finite resources, and theoretical concerns reflect underlying needs of all of these groups.

“Put the user needs above all,” is a deeply important and even radical idea. The reality of app development has long put control into the hands of platform landlords, and third parties that control every aspect of interaction from the UI to the network to the data, and is in no way bound to an ethic of putting the user needs first. In fact, it’s clear from the trends in mobile software and social media that exploitation and manipulation of the user for profit are par for the course.

The Internet is for End Users

If we continue the trail, we can look at the referenced RFC8890, better known by its title, “The internet is for end users”.

For example, one of the most successful Internet applications is the Web, which uses the HTTP application protocol. One of HTTP’s key implementation roles is that of the web browser -- called the “user agent” in RFC7230 and other specifications.

RFC7230 was the latest spec for HTTP1.1 at the time. If you look in that document, you can see how it defines “user agent”.

The term “user agent” refers to any of the various client programs that initiate a request, including (but not limited to) browsers, spiders (web-based robots), command-line tools, custom applications, and mobile apps.

So there you go, its just a fancy term for “client program”, right? Well, let’s go back to RFC8890 to see what else it had to say.

User agents act as intermediaries between a service and the end user; rather than downloading an executable program from a service that has arbitrary access into the users’ system, the user agent only allows limited access to display content and run code in a sandboxed environment. End users are diverse and the ability of a few user agents to represent individual interests properly is imperfect, but this arrangement is an improvement over the alternative -- the need to trust a website completely with all information on your system to browse it.

Defining the user agent role in standards also creates a virtuous cycle; it allows multiple implementations, allowing end users to switch between them with relatively low costs (although there are concerns about the complexity of the Web creating barriers to entry for new implementations). This creates an incentive for implementers to consider the users’ needs carefully, which are often reflected into the defining standards. The resulting ecosystem has many remaining problems, but a distinguished user agent role provides an opportunity to improve it.

These two paragraphs are really outlining a couple of very important ways in which end user needs can actually be put first in clear details.

A user agent is an intermediary. Any program can be a client program to a server program. What makes it a “user agent” is that it acts on behalf of the user, and is able to protect the user from potential harms. Arbitrary executables are dangerous. A user agent enables a sandbox environment and protection from these kinds of dangers. It also operates under a kind of mandate to the end user, taking responsibility for establishing and maintaining a safe environment, even in the face of developers trying to cause harm.

The user agent is a deliberate abstraction allowing for multiple implementations. As Cory Doctorow has pointed out in his book, “Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It”, internet companies lean heavily on platform lock-in, making switching costs incredibly high. This is the tool of enshittification. Standardizing the role of a user agent, and having multiple implementations, prevents the lock-in in the first place.

Failures of the User-Agent model

Despite all the best intentions of the web platform’s design principles, and the many man-years of labor making browser engines incredibly sophisticated sandboxed execution environments, there is still a fundamental problem with the model. A kind of loophole. It is well described by Robin Berjon in his article on Web Tiles (which we’ll actually circle back to later). He says,

Capping this off, RFC8890 explains — quite correctly — that you don’t want online services to be able to run arbitrary code with arbitrary access to your system. That makes intuitive sense, but there’s a loophole: it implicitly assumes that what you care about, and most notably your data, is on your system. What happens if essentially all the data that matters most to you is not on your system but on someone else’s? In that case — which is the common case today — the current browser-based user agent paradigm will not protect you from arbitrary access. Most of the time you’ll have no option other than to trust some company that, more often than not, you know isn’t trustworthy.

Sad facts. But how did it even get that way? Failure to apply design principles? Nefarious implementors? It doesn’t have to be so extreme. Corey Doctorow explains the whole process. At first the companies provide genuine value. Then as growth slows, extraction begins. You know the rest. The history of Silicon Valley is littered with the bodies of better angels of visionary co-founders.

In the beginning, Google provided an incredible amount of value in its email and drive and doc products for free. And Facebook allowed people to share pictures and connect with friends. And Reddit gave an easy UI and user control over the old usenet forums and bulletin boards of the early web. And WhatsApp emerged as a global cross-platform messaging service people actually used. Value, value, value, value. For free. But in the end, you realize you own and control nothing, and the seemingly open and independent web has come under the full control of techno-feudal lords. For a while, there was a commons, but that too has been enclosed.

The problem with creating an empty, safe, sandbox, is that its pretty boring. You can safely consume, but you cannot participate. In order for you to participate you have to actually move your data into the sandbox, and this is where you hit the primeval roadblock. Where do you put it? The web browser, as a User-Agent, is very poorly equipped for this purpose. It has no concept of identity, or data that belongs to you and not a web application (securitized with the single origin principle). How would you share your pictures or thoughts on the latest marvel movie, unless you fully gave that up to a third party to hold and serve for you. Multiply that times everything, and that’s where we are.

Back in the heady days of “Web 2.0” starting about 2004, there was a gold rush of new websites, services, and platforms that were eager to be the requisite server needed to hold your stuff. This is right when I graduated college and was jumping into web development myself. Firefox had risen up, the engines were moving again, CSS and standards mattered, REST had won over SOAP, AJAX was a new hot concept in dev, SaaS was the new playbook, and Social Media was about to explode. Also really important of note, is that within the more experimental circles, the vision of the future was clearly “mash-ups”. With all of this data moving online, and everything being potentially accessible through RESTful APIs, and browsers being able to fetch data from multiple sources and build integrated UI’s on the fly, it seemed only a short matter of time before we might live in a kind of utopian web of integrated services and data that could all talk to each.

This was also around the time that IIW first got started, because it was clear that this new age of the internet would need better concepts of identity, and infrastructure for trust, or else we would not like the future we lived in.

In 2008, Jesse James Garret, UX Designer and coiner of the term AJAX, collaborated with Mozilla on a concept called Aurora. You should treat the video a bit like a “concept car”. Nobody was actually building it, but it was a way of demonstrating complex ideas and interactions in a future where Apps almost disappear into building blocks for a mashup web future. The internet of the things. Open data. E-commerce. Identity, and parent/child data security. It is a vision where all of the potential data, interfaces, and actions available across the internet (and beyond) related to you, are accessible at your fingertips everywhere, and with an implicit sense of sovereignty, privacy, and accessibility.

That is not the future we got. Venture Capital giveth, and Venture Capital taketh away. As the 2000’s became the 2010’s, we saw a radical increase in corporate consolidation, surveillance capitalism, and walled garden practices. Then came the 2020’s and generative AI. And now, in a world where we never solved the problems properly of identity, trust, or data-sovereignty, we’re seeing an exponential growth in bots, spam, fraud, scams, and misinformation. AI generated content now outpaces human generated content, and bot traffic outpaces human traffic.

With the addition of AI summaries for search engines and the rise of simply using AI instead of search entirely — we are seeing a dramatic plummeting of human page-views. The economic model that Google helped establish in the 90’s is officially dead. And all of the services holding your data and contacts have closed up, because they don’t want to give it to the AI for free, and the services themselves don’t want to compete with alternative interfaces. Twitter/X and Reddit, for example, originally shining examples of free speech and open API’s, are now all closed up. X doesn’t even want you sharing links, the fundamental commodity of the web, because it would mean enabling you spend time elsewhere.

Hope of the User-Agent model

It may seem hopeless to fight enshittification, but I believe there is also opportunity. Web Browsers and the Politics of Media Power is a recent article by a former Mozilla volunteer writing under the name Lyre Calliope. They articulate the role of browsers in the modern landscape:

Browsers were never just software to me. They represent freedom, exploration, and possibility. They are how I learned to think, create, connect, and organize. I grew up alongside the open web, and I felt, before I could even name it, that the browser was where the rules of that freedom lived.

Over time I noticed a pattern: changes in browser capabilities shaped what got built, and what got built shaped how people interacted, organized, and imagined what was possible, both online and in their lives. For decades, the browser has functioned as a quiet, upstream site of global governance.

This is why I keep coming back to browsers as a topic of near-obsession. Not out of nostalgia, but because I’ve felt, for over thirty years, that this is a critical layer where human possibility is either expanded or constrained. And it’s still one of the few places in tech where people outside corporations can help decide which way it goes.

I’ve chatted with Lyre Calliope myself, and their passion for the concept and role of the User-Agent was influential in my choice of the term “Server User-Agent” for this missing piece I wanted to propose at IIW.

They go on to discuss in the article what a significant role the browser plays in a kind of governance role of new technology in our life. It’s been pretty sleepy in the browser space since Chrome won the last browser war. (We now all have browsers a good deal more capable than they used to be in terms of things like performance and graphics and layout. Chrome and the other browsers are much more able to deliver the application-like experiences needed for ChromeOS and the suite of web apps that Google offers.)

What is shaking up the browser space now is AI, and even OpenAI is putting their hat in the ring. We’ll see if Google let’s it happen, since all the new browsers are just based on Chromium under the hood anyway (why monocultures are bad). Lyre Calliope writes about the potential dangers coming in this new browser war:

All of this flows back to people’s daily lives. If your browser decides what loads first, what is hidden, and which AI agent shapes your choices, it is already mediating your access to information, your privacy, and your ability to organize. Every news story you read, every coordination tool you rely on, and every attempt to dissent or self govern runs through this layer.

The browser is no longer passive infrastructure. It is a front line in the fight to preserve human rights, resist surveillance, and keep open the possibility of collective self‑determination online.

This is a strategic inflection point: the rules of the web are being rewritten in real time. Whether the browser becomes a tool of public empowerment or a channel for global authoritarianism will depend on who shows up to fight for it.

Lyre Calliope was writing in August 2025, my most recent reference to so far. What they are describing, though, is a fear that has been present since long before, just in a new form. They are describing how we may be watching the Priority of Constituencies unravel. Is this AI enhancement for the benefit of the end user? Will it always be? When there is conflict between the end user and browser maker, will they prioritize the end user?

There is another kind of threat coming, described in this article which relates to a different, old, internet principle called “the end-to-end principle”. In 2004, in another document from the Internet Architecture Board, The Rise of the Middle and the Future of End-to-End, the authors discuss the importance of the “end-to-end principle” what it is and how we need to be thinking about it as the internet evolves. The authors summarize it like this:

The function in question can completely and correctly be implemented only with the knowledge and help of the application standing at the end points of the communication system. Therefore, providing that questioned function as a feature of the communication system itself is not possible.

I also like the pithy phrasing of, “Smart endpoint, dumb pipes”, from Martin Fowler about the same idea in the context of microservices. In other words, you shouldn’t rely on anything but the most basic routing and service guarantees for the transport layer. Application logic should live in the endpoints themselves. The authors also explain the reasons why it matters, primarily for the “protection of innovation”, as well as “reliability and robustness”. They were worried about the rise of the middle and the power of intermediaries. I want to highlight specifically, what they say about trust, because I think it gets to the heart.

The issue of trust must become as firm an architectural principle in protocol design for the future as the end-to-end principle is today. Trust isn’t simply a matter of adding some cryptographic protection to a protocol after it is designed. Rather, prior to designing the protocol, the trust relationships between the network elements involved in the protocol must be defined, and boundaries must be drawn between those network elements that share a trust relationship. The trust boundaries should be used to determine what type of communication occurs between the network elements involved in the protocol and which network elements signal each other. When communication occurs across a trust boundary, cryptographic or other security protection of some sort may be necessary. Additional measures may be necessary to secure the protocol when communicating network elements do not share a trust relationship.

We can’t just fix it at the end (cough cough email), and we can’t actually develop protocols without considering trust (cough cough defi) in both a hard cryptographic proof way, but also in a much softer human way.

Seriously, tho, what is a Server User-Agent?

If you actually read all of the above, you win some free internet points from me, and you’ll likely get more out of my explanation. If you didn’t, though, I think it should all still make plenty of sense. It really is an idea whose time has come, and is something that many people in the space have been feeling is missing. You can always scroll up.

So here it is, a few thousands of words later, the definition of a Server User-Agent:

Definition of a Server User-Agent:

A User-Agent that takes the role of a Server, instead of a Client.

I know that’s pithy, but after everything above, the term User-Agent should be carrying a lot of weight!

Its like the Alchemical symbols for the Philosophers stone. It can be written in a small space, but it requires a lot of knowledge to unpack properly. For those who already “get it”, the definition can be this simple sentence. They know the Priority of Constituencies and how the end user should be the highest priority for a User-Agent. They know the need for sandboxing, as well as the value of a safe, generalized runtime. They know the role that standards and governance need to play for an open, accessible internet to be possible. They also know that innovation happens when middlemen get out of the way. And finally, they know it can be difficult to get things done unless there’s money to do them. Seeing the larger systems and meta-systems affect change is the root to getting the change that you want.

In all of the writing about User-Agents above, there has always been an assumption that the User-Agent is a client. As I hope you’ve observed, this creates an incredible imbalance in the power dynamics. If users can only control agents that are clients, they will never have real agency on the internet. If instead, we imagined that for every end user, they have a Server User-Agent available to work on their behalf, there are so many things that could be done more directly, using peer-to-peer style approaches and avoiding platforms an lock in. It could single-handedly enable the inversion of the Web 2.0 platform relationships.

Of course, users have always had the option of going through some channels to set up a server as though they were an application developer. They can be a developers of their own personal server application. There are WYSIWYG application and website builders. Or even AI assistants now. There’s also docker containers and open source projects to make it easy to host your own instances of various services. Solid by Tim Berners-Lee or a Bluesky PDS is approaching a Server User-Agent, but lacks the complete requirements to fit the need. In a way, these are all helping fix a gap, but none of them are Server User-Agents as I’m proposing.

While at IIW, if I was trying to quickly summarize what a SUA is, I would say something like, “your browser in the cloud”. It helps convey the idea of a generalized, sandbox runtime in the cloud, that can handle requests and perform functionality on your behalf. I just don’t want to cause a direct confusion of browser functionality. The browser has a DOM and a UI and input events, etc. This Server User-Agent, instead, would fill the infrastructure gaps that prevent web applications, or even native application, from easily being first class citizens of the internet, and interacting with sovereign identity and data and trust networks.

What is Needed

There is a famous essay by Richard Gabriel called, The Rise of Worse is Better. It explains a kind of approach to development priorities:

The lesson to be learned from this is that it is often undesirable to go for the right thing first. It is better to get half of the right thing available so that it spreads like a virus. Once people are hooked on it, take the time to improve it to 90% of the right thing.

It sounds like the Silicon Valley model. Minimum Viable Product. Iterative development. Agile even. Growth hacking. But especially for public infrastructure, it can also lead to unintended consequences that cause harm, and useful problems that stay locked in place. It only gets to 90% of “the right thing” if it actually keeps improving in that direction. The stories of the browser wars show that this is not a guarantee.

We’ve gotten “worse is better” User-Agents, and while they are more capable than ever, they still seem incapable of getting us to “the right thing”.

Richard Gabriel wrote a followup essay later, called Worse is Better is Worse, under a pseudonym. In this essay, he provides a more nuanced look at the false dichotomy, and especially skewers the popular quote above, saying:

This advice is corrosive. It warps the minds of youth. It is never a good idea to intentionally aim for anything less than the best, though one might have to compromise in order to succeed. Maybe Richard means one should aim high but make sure you shoot—sadly he didn’t say that.

“Aim high but make sure you shoot.” I like this much better. I think it shows the real tension between getting it right, and waiting so long you miss out.

I have to admit that I’m a bit of an Alan Kay fanboy, but I also can’t help but feel shaken by his cries that the computer revolution still hasn’t happened, or that we’re writing way to much code to express ourselves, or that software engineering is an aspirational term.

In his 2015 talk, Power of Simplicity, he talks about something that I feel like is a response to this “worse is better” conversation. He talks about “what is needed”. I linked right to the relevant part of the talk, its all the way at the end. If you have time, watch the whole thing, its great.

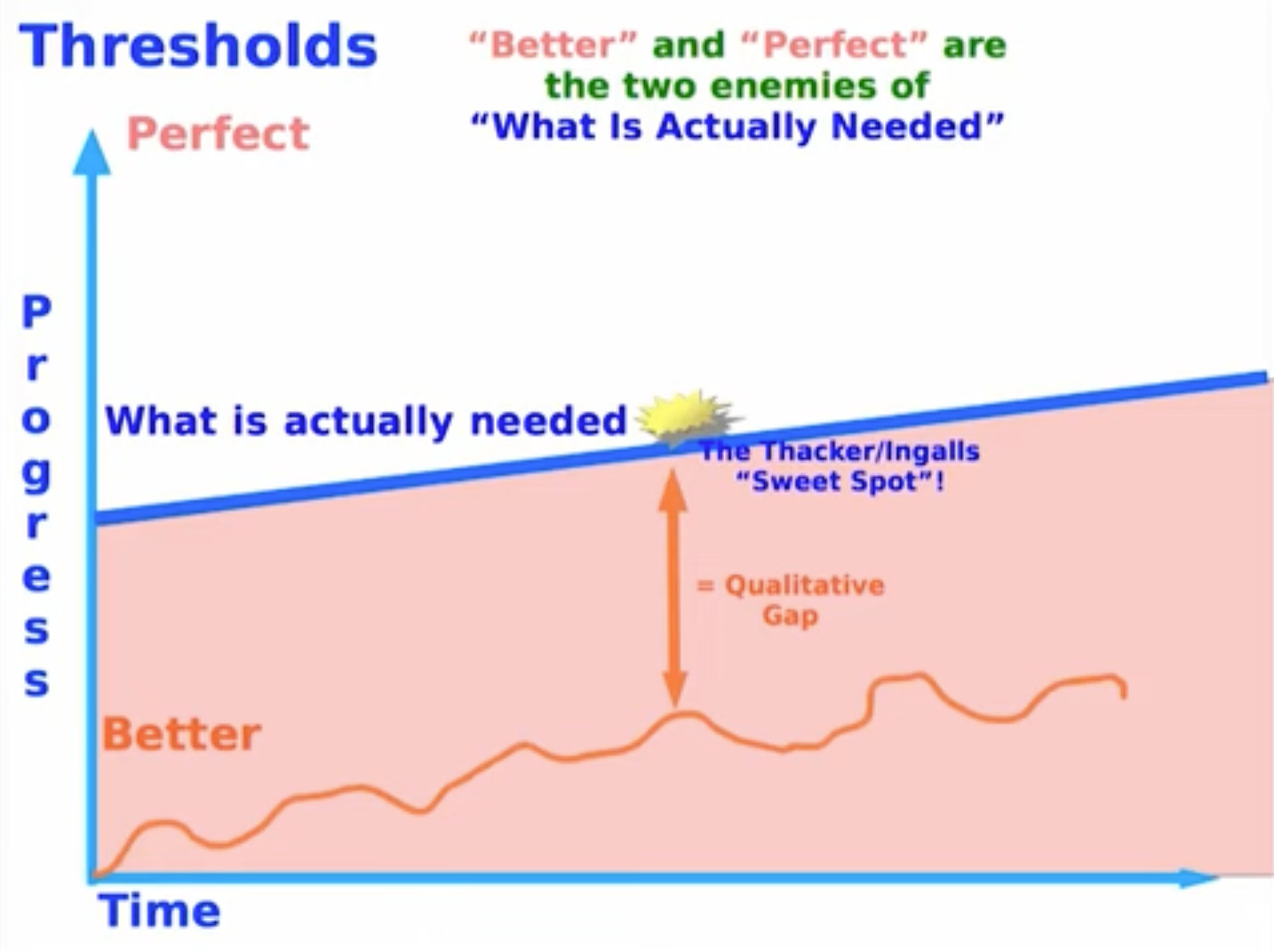

Kay talks about the idea of thresholds and progress against time. He uses test scores as an example. Its a metric that can be measured to go up — to have a sense of progress. But as he says, “There are many many things, where you have to get to the real version of the thing before you’re doing it at all.”

He says that “Perfect” and “Better” are BOTH enemies of “What is actually needed”. The real trick is to find that sweet spot, just over the line of what is needed, and from there, you’ll make a leap of genuine progress. I believe that for the internet, especially in the year 2025, that sweet spot is Server User-Agents.

We can’t have Agency without Server User-Agency!

I’ve tried to make the case in the section on User-Agents that the goal of them is fundamentally good, and worth fighting for. We’ve observed the lessons of human history since even before technology, and can understand the systemic issues with unchecked monopolies or platform control.

In the last decade, especially, we collectively have learned more viscerally what we gave up when we let big tech corporations hold all our data for free. We learned from Cambridge Analytica, and the effects of algorithms, and the loss of trust, and the spread of misinformation. We learned it is disempowering not to control your identity or your data or your communication channels and contacts. We learned that the internet is real and has consequences, and a disturbing lack of ability to easily self-govern and build trust.

These problems have been fairly obvious to many for a long time. The Internet Identity Workshop itself and all the work they have collectively done for 20 years is a testament to that.

The core problem I have seen is that local-first or client-only solutions have real trouble scaling to the whole global internet. There are often needs for discovery or searching or aggregation or relay or trust or availability, etc. If we expect to have true User-Agents for the internet at all, we have to recognize that we’ve alway been limited to partial agency. We’ve had the manacles removed from our wrists, but not from our ankles. We can work, we can create, we can consume, but we lack the ability to move freely and choose the terms under which we participate.

Missing Pieces of the User-Agent

At this point of the article, my hope is that your mind is already in motion, thinking about what the shape of this Server User-Agent could be. I’ll go through some missing aspects of the User-Agent that I think can be solved with the help of Server User-Agents.

Identity

This is an obvious one for anyone coming to IIW. The browser has absolutely no mechanism for storing and using identity. From the very beginning of the Web, there was a need to lean on email as a mechanism to bootstrap identity. This reinforced email long past its prime. Worse, the email-password combo has caused endless identity and security problems.

Over the last two decades of work, the problem has been approached from many angles—OAuth for authorization, OpenID for federation, VCs and DIDs for sovereignty—but they all share a common gap: they still require some server to anchor your identity or mediate your relationships.

For example, DID:comm is well defined and supported, and could be used right now. It’s just that the transport itself is pretty abstracted away. You want to do it over wifi or bluetooth? No problem. You want to do it across the internet? How?

With an SUA, your identity can live in infrastructure you control (or delegate control of, but with real agency). Your DIDs resolve to endpoints you manage. Your Verifiable Credentials are presented by agents acting on your behalf, not by hoping the website implements the right protocols. You get actual many-to-many choice in terms of where you get your credentials and who you might present them to, that stays within your control.

With a browser, we have to assume ephemeral storage with low limits, but I would expect a SUA to have a digital wallet and attached storage as well, solving another major issue. Additionally, in a future of cryptographic identities and communication, I would expect support for managing cryptographic keys.

Relationships

Not only do we typically have to create a new account with every service, but we need to replicate our social network each time as well. We have to hand over our relationships to the hands of third parties. This creates a massive lock-in effect. And if you ever get locked out, like if your account gets blocked, you lose access to all of those relationships.

There are many serious efforts within the identity space, such as the First Person Project, that have laid most of the groundwork needed, for example, to create decentralized trust networks for social verification. They mostly just need to work with digital wallets and DIDs. The problem with only having wallets on client devices is that transport layer problem again. If each person had their own SUA, the same kind of peer-to-peer model would work much more seamlessly and with resilience to device loss, etc.

The protocols for cryptographically provable relationships are ready —Alice can prove she knows Bob, Bob can attest to the nature of that relationship, and both can do so without a platform intermediary. But these credentials need somewhere to live and something to present them on your behalf.

Data Fiduciary

To move into the full value of a User-Agent for the internet, we have to be able to bridge that tension between the sandbox of the application, and the data that we might want it to operate on. As discussed above, the fundamental loophole is that we just have to give up all our data into the sandbox.

On the other hand, it is also the case, that average users don’t want to manage servers or infrastructure or happen to have data center in their closet. The Mozilla Aurora concept video showed off how powerful it could be when we can share our data, or mix it with others data. We might want to have our SUA hosted in the cloud, but still have the obligation for the host to act in our best interest. In the future you may be able to avoid filling out any forms, but simply granting access to your data to different parties. A far cry from the freewheeling days of mashups and no security, if we want to do it right, we’ll need stronger primitives for storing, accessing, and sharing data on our SUA’s.

I think the term fiduciary is useful in both a hard legal, and softer metaphorical way. In the softer way, we may have to think about roles, access, and responsibility to data for your best interest without a legal enforcement, as well as with.

In the soft sense, the term fiduciary works similarly to the priority of constituencies. End user best interests. We don’t want to design this with the application developer or User-Agent developer as priority. We must make sure it meets end user needs. The limits of single-origin principle may work for the browser, but not Server User-Agents. This is certainly an area that will need a lot of development.

One thing to consider could be protocols like JLINC for cryptographically signed data exchange agreements; where each party has a cloud agent acting as their representative. Instead of vague terms of service, you get human and machine-readable contracts that specify exactly what your fiduciary can and cannot do with your data—with every transaction logged and auditable.

These agreements could go between you and third party application, but they could also be used with the Server User-Agent cloud host itself. Your SUA provider is your fiduciary—they operate infrastructure on your behalf, but under explicit contractual terms you’ve signed. Standard Information Sharing Agreements (SISAs) could define what responsible fiduciary behavior looks like for different contexts, negotiated by user advocacy groups and service providers.

I’m new to that area, though, so I welcome feedback.

Data Synchronization

Cloud backups or synchronizations have become a kind of expectation for users these days, and feels like a solved problem when it comes to simple, single user backups. iCloud, Google Drive, Dropbox. I want to talk about this subject in two ways: backups, and synchronized sharing.

Backups/Storage

If you want to make a simple iPhone app — let’s say its something simple like a journal or a personal calendar, all of the logic could live completely in the app, with no servers. You could save data locally, and the iCloud service would save a backup. This is the potential of local-first. It works offline, it scales more easily. But iOS/iCloud is doing some of the work here, and it won’t translate to the web.

Local storage for browsers is well known to be unreliable beyond minimal load. The browser is meant to be ephemeral after all. This creates real problems for any web-based local-first approach. It would make sense for SUA’s to have storage capacity that would allow for more reliable, application owned data. Ideally it should not be bound by same-origin policy, but rather be able to participate in fiduciary managed access. Store data. Share data. Load a web game off of a neocities page, and allow it save to your SUA, and re-open the game from another device. This should all be easily possible with an SUA.

Synchronized Sharing

The other kind of synchronization that, I think, is even more powerful is when we get into live collaborative editing, or shared game states. CRDTs, Operational Transforms, or even basic game server input replay are all common patterns for coordinated shared state. All of them could benefit in some way with SUA’s.

SUAs don’t replace local-first or peer-to-peer protocols—they complement them. Local-first gives you ownership and offline capability. P2P gives you direct connections when possible. SUAs provide the persistent, addressable, always-on infrastructure that makes everything else work reliably at internet scale.

Last Mile Internet Problems

I’ve already covered specific flavors of this problem, but I wanted to name the general problem. You want to send someone a message, share a file, make a video call, or coordinate in real-time—but you hit fundamental infrastructure barriers.

Email solved this decades ago by accepting a trade-off: messages go through intermediary servers that can read everything. Modern alternatives like Signal or Matrix improve on privacy, but they still require someone’s server to relay messages when recipients are offline or behind NAT. You can’t just directly reach someone’s device most of the time because of firewalls, dynamic IPs, and the reality that phones and laptops aren’t always on.

Peer-to-peer protocols like WebRTC can establish direct connections when both parties are online simultaneously and network conditions allow it. But the “when conditions allow” is doing a lot of work. In practice, you need STUN/TURN servers for NAT traversal and relay servers for when direct connection fails. Who runs those servers? Who pays for them?

This is where Server User-Agents solve multiple problems at once. Your SUA is your persistent, addressable endpoint on the internet. When someone wants to reach you, they connect to your SUA. But more than that—your SUA can act as your STUN/TURN server when needed. It’s infrastructure you control (or your fiduciary controls on your behalf) that can facilitate peer-to-peer connections between your devices and others.

This doesn’t eliminate peer-to-peer—it makes it actually work reliably. The SUA provides the discovery, coordination, NAT traversal, and fallback relay that the last mile requires, all under your control rather than relying on free services that could disappear or paid services that create vendor lock-in.

Artificial Intelligence

The explosion of AI capabilities over the last few years has made the lack of Server User-Agents even more glaring. Right now, every conversation you have with ChatGPT, Claude, or any other AI lives in their infrastructure. Your conversation history, the context you’ve built up, the preferences you’ve established—it’s all locked in their systems.

This creates the same problems we’ve seen with social media. Want to use a different AI? Start over. Want to give an AI agent access to your calendar to help schedule? Hand over your Google credentials. Want an AI to help you write based on your previous work? Upload it all to their servers where it might be used for training.

Server User-Agents could change this fundamentally. Your conversation history with AI assistants lives in your SUA’s datastore, not scattered across different company servers. You control what data an AI can access and under what terms—using the same cryptographic agreements (like JLINC) that govern human data sharing. An AI agent helping you could access your calendar, your documents, your contacts, your preferences—all mediated through your SUA with explicit, auditable permissions.

Beyond personal assistance, AI agents working on your behalf need infrastructure to operate. They need to make API calls, coordinate with other agents, maintain state across long-running tasks. Your SUA becomes the natural home for these agents—they operate under your control, with your resources, following your directives.

It’s hard to imagine the future of AI agents working at all without something like SUAs. How else would an agent persistently represent you on the internet, maintain your context and preferences, coordinate with other people’s agents, and do so under terms you actually control? The current model of “give all your data to Big Tech and hope they build good agents” isn’t a viable path to user agency.

Restoring the End-to-End Principle

Earlier I talked about the end-to-end principle and I quoted from RFC3724 about it. I bring it up again here, because I think SUA’s could be the missing piece for restoring this principle. The RFC said that “the issue of trust must be as firm an architectural principle in protocol design for future as the end-to-end principle is today.” There is almost no trust left on the internet and it is specifically because of these failures in protocols and infrastructure. The User-Agent has not been able to protect the end user. Trust has been broken. Not because of the internet itself, but because of the third parties we have had to put our trust in for lack of a Server User-Agent.

The modern internet is dominated by powerful intermediaries who control not just the pipes, but the entire application layer. Facebook isn’t just routing your messages—it decides what you see, who you can reach, and under what terms. Google isn’t just helping you find information—it’s deciding what information exists and how it’s ranked. These platforms have become the new “middle,” and they’re anything but dumb.

The original end-to-end principle assumed that endpoints were capable—that they could be servers as well as clients. But as we moved to mobile devices, NAT, and restrictive networks, our endpoints became hobbled. Your phone can be a client, but it can’t reliably be a server. So we had no choice but to put everything in the middle.

Server User-Agents restore the end-to-end principle by making endpoints capable again. Your SUA is your endpoint on the internet—always addressable, always available, able to send and receive without intermediary gatekeepers. When you communicate with someone else’s SUA, it’s endpoint-to-endpoint, even if both SUAs are operated by fiduciaries. The application logic lives at the edges, where you control it.

This isn’t about eliminating all intermediaries—fiduciaries and infrastructure providers will always exist. It’s about ensuring that intermediaries can’t unilaterally control your digital life. With SUAs, you can switch providers, export your data, maintain your relationships, and run your applications without permission from platform monopolies.

Web Tiles (or something)

When I talked earlier about the failures of the User-Agent model, I quoted from Robin Berjon’s Web Tiles article where it discussed the loophole problem of the sandbox. Where we have to put all our data in the sandbox.

Berjon proposes, in the article, a new primitive called a Web Tile. The quick definition goes like this:

A tile is a set of content-addressed Web resources that, once loaded, cannot communicate further with the network.

I reference Web Tiles, not because I want to directly endorse it wholesale, but it seems like a good place to get started as a kind of primitive we need. I agree with most of the goals and requirements as stated. We need to be able to better leverage web technologies, including UI, in secure ways that don’t depend on origin-served content. There are also ideas I like in here about content-addressing that makes sense. There are a lot of virtues to that approach.

Imagine if web tiles could guarantee not to exfiltrate, but then that would allow safe access to private data that could be stored by your Server User-Agent. Access could be done using object capabilities instead of free network access—the tile gets explicit, revocable permissions to specific resources rather than blanket network privileges. It could even work with the fiduciary concept.

It also seems possible to make a Tile with both client and server code running on both the local-client and Server User-Agent, somewhat like a Roblox game or React Server Component. It could even be possible to compose multiple tiles within a single view.

This will take a lot to get right, but seems worth exploring.

Shape of a Server User-Agent

This is so early that I don’t want to overspecify anything. I’ll just close this out by trying to describe the vague shape of a minimal Server User-Agent. None of this is in stone.

It should be something that could be self-hosted or cloud hosted.

It should be able to be assigned a custom domain.

It should be able to respond to (at least) the breadth of protocols that a browser uses (http, web sockets, server-sent events, etc)

It may be able to act as a STUN/TURN server

It should be able to install some flavor of Web Tiles (packaged, sandboxed, content-addressed, web content)

These packages would likely come in two flavors: extensions vs tiles.

Extensions - require more trust and would be able to connect to the outside world, implementing new protocols, directly handling external requests etc.

Tiles - more like the original proposal. Can only interact with the capabilities it is given. Cannot exfiltrate.

It should have a digital wallet

It should have persistent storage capable of handling a variety of storage needs

It should be able to manage keys and signing operations

It should be able to act as an ATProto PDS or speak ActivityPub

I think you could imagine that, depending on the hosting situation it may have set limits on the extension or tiles or whether it would offer STUN/TURN or other service limits, but it should still fit the same standards.

Just to give a little example of the potential, consider ActivityPub. Right now, there are some challenges in the fediverse. Different content types like notes or videos tend to use different apps with different accounts, etc. With a combination of Server User-Agent and tiles, you should be able to have a single actor that maps to your SUA, can publish any kind of content, can store it in your own database, and then use the appropriate tiles to actually look at them. Why have a whole ass application when almost everything is the same. And then to still have kludgy stuff like everything being a Note so it shows up in Mastadon. Your SUA becomes your unified presence across protocols, with applications becoming just different lenses on your data.

What’s Next

There’s a Signal group and a lot of work to do. Follow me here for updates or poke me on Bluesky @whenthetimeca.me if you want to join the group.